CHANGING HABITS: WHAT BRANDS CAN LEARN FROM TOOTHPASTE MARKETING

Viviana Molina Burbano

25/01/2022

In the early 1900s, an advertising executive achieved the seemingly impossible: he made using toothpaste a worldwide habit. His strategy is one that modern marketers would do well to learn from, writes Viviana Molina Burbano.

Prior to the 1900s, toothpaste was widely available but rarely used. It wasn't until Claude Hopkins was approached by the brand Pepsodent that the product became a massive hit. At the time, taking on this project was a risky move, as (despite the nation’s declining dental health), toothpaste was seen as a gimmick rather than a necessity, with only 7% of Americans owning a bottle.

So what made Hopkins achieve the seemingly impossible?

He leveraged the psychology of habit formation to create a new ritual across the United States. In the book The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg explained how Hopkins was able to leverage a simple cue and a clear reward to create a “neurological craving.”

This wasn't a completely new strategy for Hopkins, in fact, he was known for choosing a simple trigger to promote the use of the world’s biggest brands. For example, he had previously promoted Quaker Oats as an energy producing cereal that required daily consumption to be effective, which made the brand a massive success. But what made the Pepsodent strategy special is that in it he identified that what people want and what they need are two different things - and that the first could be used as a means to achieve the second.

After reading several dental textbooks, Hopkins realised the main issue with toothpaste marketing: they were full of promises like "neutralises salivary deposits" and "allays inflammation." Promises that might excite a dentist, but not an average consumer. (Below ad from 1901).

From his research, Hopkins identified a more interesting benefit: Plaque causes yellow teeth and yellow teeth are ugly.

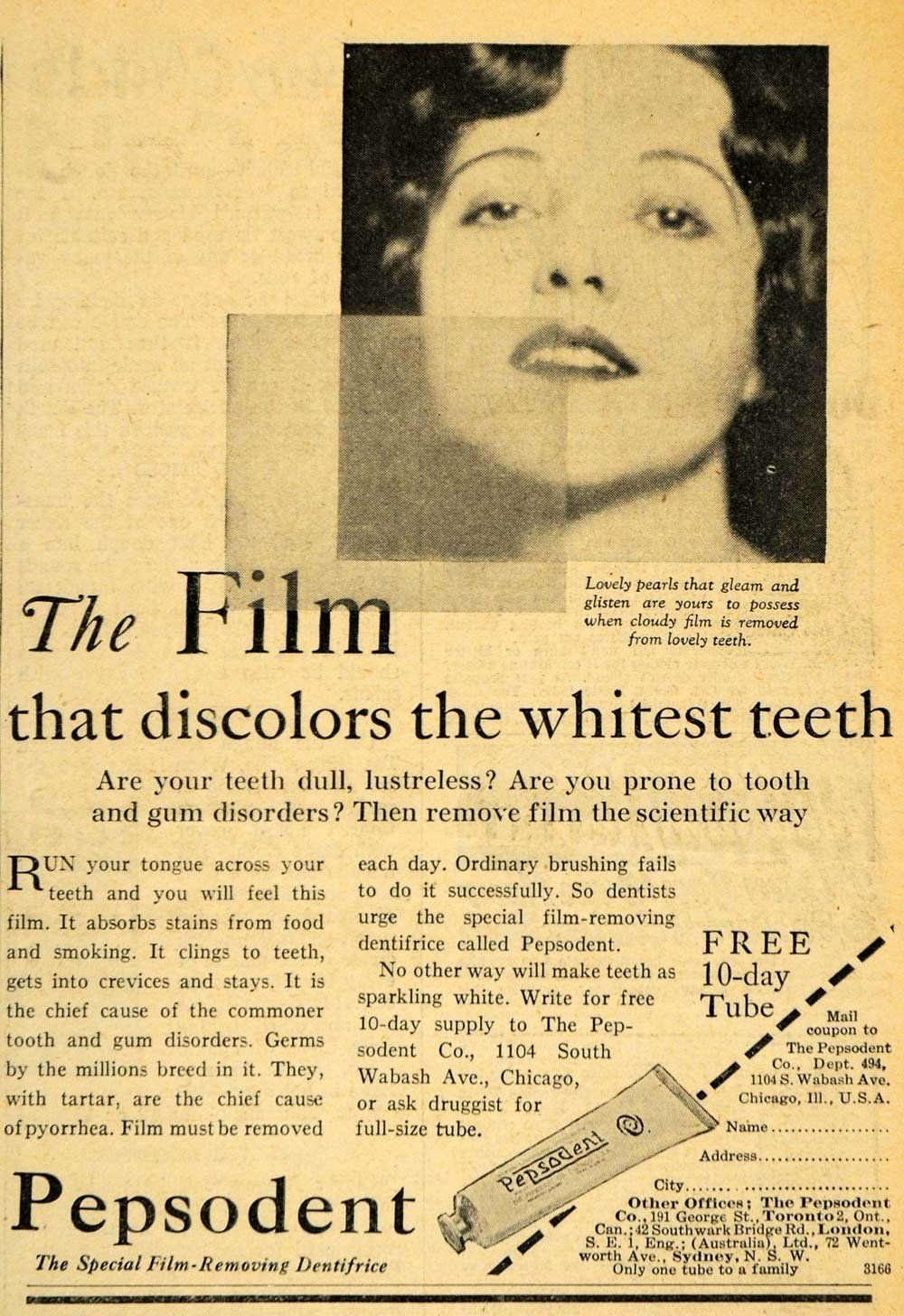

Knowing beauty was a priority, especially for women at the time, he decided to rebrand “plaque” by calling it “film” and positioning it as the culprit for ugly decaying teeth.

“That gave me an appealing idea. I resolved to advertise this toothpaste as a creator of beauty.” - Claude C. Hopkins.

And he did so in a way most brands fail to, by making the CTA the cue to a habit rather than a cue to a one-time purchase.

What does that mean?

While most brands lose money by focusing on boilerplate, brand-focused CTAs, Hopkins asked his audience to look inwards and use Pepsodent as a way to enhance something already inherently valuable to them- their looks.

Aside from the misogynistic tone of the copy, the ads were brilliant for the time. The message was simple, yet effective and it gave both the audience and the brand a common enemy- dental film. And most importantly, it gave people a daily cue (the tongue test) for a habit that required toothpaste to be fulfilled, while also tying it to a reward (beauty) that requires maintenance.

It worked like a charm. Three weeks after the first Pepsodent ad campaign, the brand had more demand that it could keep up with. And in as little as three years, the product went international, later becoming one of the top sellers in the world.

There is certainly a lot to learn from the Pepsodent strategy, not only did Hopkins choose a benefit that truly resonated with his audience, he leveraged it to create habit-driven CTAs, ensuring the longevity of the campaign.

However, the real magic in this story lies in the product itself. Ten years after it became a household name, competitor toothpaste brands went on a mission to research why the company was still so successful. To everyone’s surprise, it wasn't just the famous campaign that made people crave the brand, it was the sensation created by its unique recipe. Turns out the citric acid and mint oil used to make Pepsodent created a tingly sensation in the mouth - a feeling customers craved as it became associated with cleanliness. That craving is essential for habit formation and it was a part of the product all along.

So what can we learn about toothpaste, science & behavioural change?

Before we get into it, it’s worth noting that times have changed and with messaging coming from multiple channels, solely rational thinking will not cut it. All work should inspire some type of emotion to truly resonate, and for that you also need creativity. With that said, below are some ways you can incorporate this habit-making approach into your campaigns:

Find what your audience needs, but communicate what they want (i.e. Quest protein snacks messaging around great taste, rather than dietary benefits).

Think about your audience’s current habits. Is there a way your brand can add value to their current routine? (i.e. Cuisinart's drip coffee maker lets you schedule brewing up to 24 hours in advance).

Think about current/potential cues and rewards that encourage your audience to build a habit around your product. (i.e. when people are at a beach (cue), they think of Corona, and in that case, the sensation from the beer acts as the reward).

Get creative with your CTAs- don’t feel restricted by your typical “download now,” if you can, leverage those cues and rewards to encourage consistent use.

And most importantly, never stop researching- as we learned from Pepsodent’s story, you may be well established, but your success could be attributed to things you are yet aware of- don’t let your competition find out before you do.

Sources:

https://medium.com/@merijoanna/how-a-person-taught-the-world-to-brush-their-teeth-story-of-pepsodent-3dc853bdd715 | The Power Of Habit | Charlesduhigg.com