THINKING DIFFERENTLY ABOUT THINKING DIFFERENTLY

APARNA BANGUR AND GEORGE NAGLE

11/06/2023

Different thinking is the lifeblood of the advertising industry - and yet agencies have failed to make a home for different thinkers. It's time, write Aparna Bangur and George Nagle, we took neurodiversity seriously.

The Sistine Chapel. The Theory of Relativity. The Little Mermaid.

Neurodivergent people have shaped the world around us.

And of course they have. Neurodiverse people experience the world differently to most, and that fresh perspective is where creativity comes from. To paraphrase the old BBH mantra, difference has the power to make a difference.

The advertising industry, and the UK in general, is in desperate need of that creative magic right now.

So what are we doing to best attract the 20% of the population classified as neurodiverse?

The stats are shocking.

Only 10% of organisations factor neurodiversity into their HR policies (Creative Equals, CIPD Report 2022).

50% of neurodivergent people in the UK have felt excluded or marginalised at work (Belonging: The Key to Transforming and Maintaining Diversity, Inclusion and Equality at Work).

What’s holding us back?

We are stuck in some bad habits. Affinity bias prompts us to employ ‘people like me’, because we feel awkward around someone who isn’t.

And so, saying “can’t” comes far too easy to us.

Can’t hire different people, because we attract what we are.

Can’t adapt our work culture, because the unfamiliar feels uncomfortable.

Can’t support invisible issues, because we often don’t look deep enough.

Policies and processes make candidates feel marginalised, pitied or at a disadvantage generally.

Common employability criterias also screen out neurodiverse people. Solid communication skills, being a team player, emotional intelligence, persuasiveness, salesperson-type personalities, the ability to network, the ability to conform to standard practices and so on.

Not exactly a neurodivergent person’s forte.

And then there are interviews!

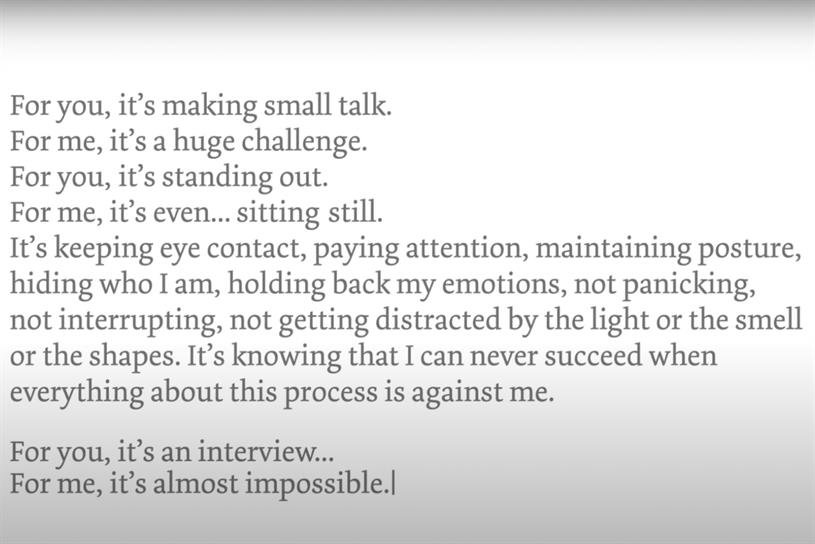

The ugly truth is that traditional interviews recruit for social skills rather than job skills. Autistica’s recent campaign underlines just how massively the process is stacked against neurodivergent applicants.

George Nagle, a Strategist at BBH who has been diagnosed with autism, confirms this:

“Autistic people struggle not because they can’t fit the role, but because the process of getting hired is actively challenging for them. In an industry where creativity and abnormal thinking is heralded as the secret weapon in a never-ending cold war of advertising pitches, some of the most creative and (positively) abnormal minds are falling through the cracks just because they aren’t as comfortable in social situations as the average person.”

DIFFERENCES ARE NOT DEFICITS

The idea of competitive advantage is intrinsically linked to difference.

It’s the people who don’t fit because they have a different way of seeing, thinking and doing that make more interesting work. They are problem solvers, because their everyday life is beset by obstacles to overcome.

From a personal lens: when my son was diagnosed with autism, initially my heart sank, but eventually my world got bigger. I was able to uncover more of life’s less-explored but fascinating layers. It started with looking at his differences as strengths. For instance, his “love of repetition” translates to an excellent memory and his “need for sameness” makes him strong at detecting patterns.

George has found much the same:

“From bad puns to carefully constructed gags, to the quirky GIF or sentence in a strategy deck - humour has always been my go-to replacement for natural speaking charisma. People don’t care if you’re awkward if they like being around you. My imagination is another one of my traits supercharged by my condition. Whenever there’s a lull, my brain jumps in with new stories and hypotheticals that it just loves to play out. Great when it comes to fuelling creative discussions and constructions.”

If you focus on can't then only ‘can't things’ happen. Whereas if you focus on what can, more often than not, expectations are exceeded. This is the starting point in our journey from othering to true inclusion.

Let’s move from interrogative interviews to friendly conversations.

Let’s stop searching for flaws, and start playing to strengths.

Let’s think differently about those who think differently.