PEAK NOSTALGIA: WHY GEN Z ARE BECOMING FUTUREPHOBIC

Megan Cullen

21/03/2022

The future needs to hire the past's advertising agency. Megan Cullen (Senior Strategist at BBH USA) explores the rise of futurephobia and its role in driving the nostalgia boom.

The use of nostalgia in marketing is not a new phenomenon. Even the ad execs of the 60s were aware of its power to stir something deeply emotional within us (albeit the fictional ones). In the words of Don Draper:

“Nostalgia – it’s delicate, but potent. In Greek, nostalgia literally means ‘the pain from an old wound.’ It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone… It goes backwards, and forwards… it takes us to a place where we ache to go again.”

(Mad Men Season 1, Episode 13)

For a not wholly positive (and in many senses painful) feeling, nostalgia is strangely captivating, the sort of heartache that we crave and relish in. One of the explanations scientists have put forward as to why we seek it out so much is for its psychological usefulness: by finding solace and comfort in the past, nostalgia can serve as a kind of defense against negative feelings or ‘psychological threats’.

With that in mind, it’s no surprise that we’ve been hearing a whole lot more about nostalgia in the last couple of years, which have probably been the most psychologically threatening in our collective lives. In the first week of April 2020, Spotify reported a 54% increase in nostalgia-themed playlists being created, while old Sitcoms like Friends and Roseanne saw a huge surge in viewership from the previous year. With so much stress in the present, we turned to the past.

But looking back at the time since then, it feels like there’s something else going on. It’s not just that we’ve been (understandably) using nostalgia as a crutch in a time of need. Now, two years on from the start of the pandemic, we’ve got to the point where nostalgia is in many ways the dominant aesthetic. If you look to the trends that have defined Gen Z and young Millennial style in the last couple of years, you’d be hard-pushed to find anything that feels truly new. And, what’s more, we’re rattling through them faster than ever before: TikTok is throwing the previously accepted ‘20 year trend cycle’ out of the window.

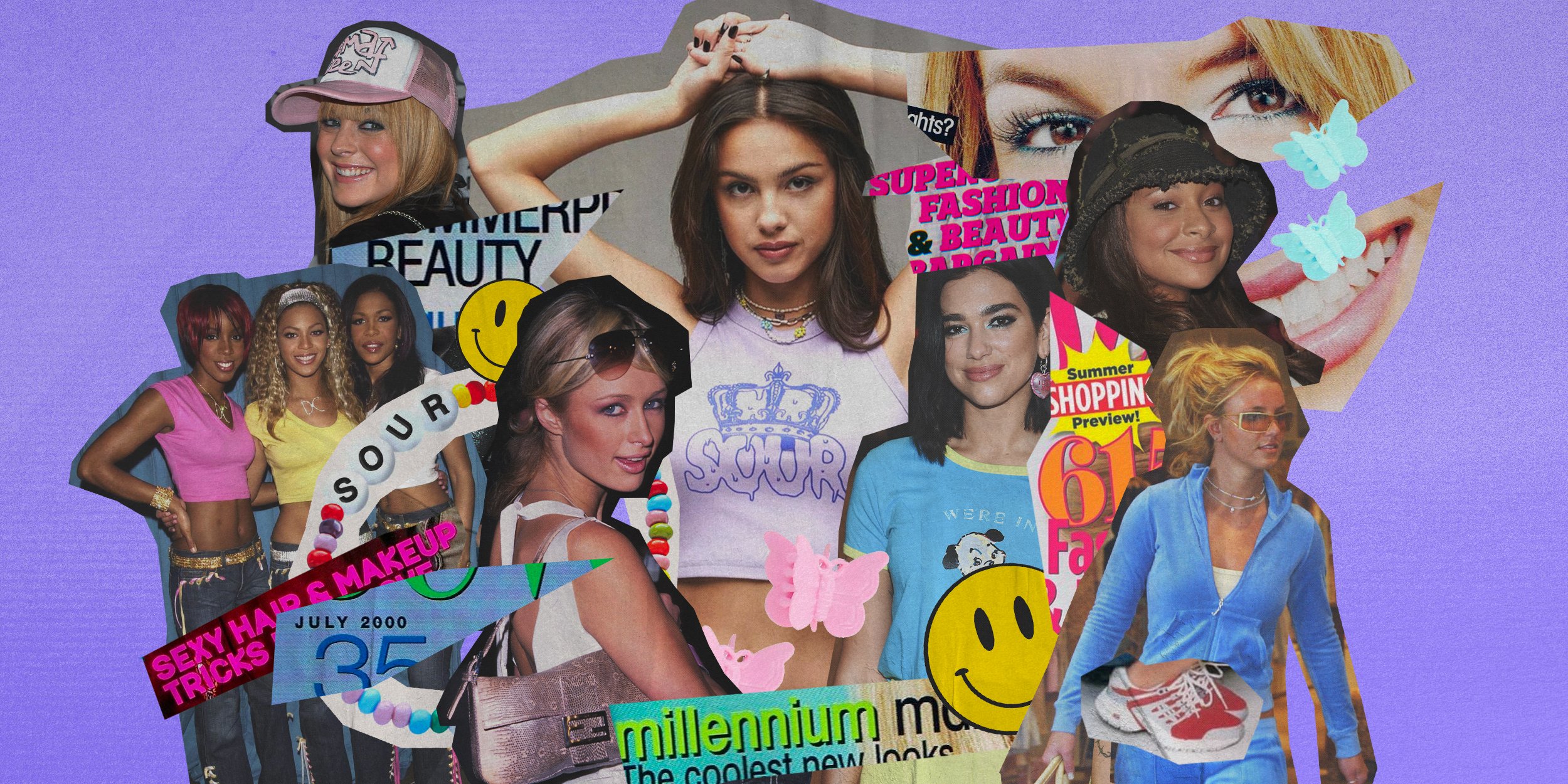

First – in early 2020 - it was Y2K: low rise denim miniskirts, bedazzled logos, and wired headphones all made a comeback, along with a resurgence in the music and TV shows of the early noughties.

Then we heard ‘Indie Sleaze’ was coming back. I didn’t know what it was either, but apparently if you just imagine walking into an American Apparel circa 2008, you’ll have a pretty good picture of it.

And now - according to TikTok - it’s all about the Twee/Tumblr aesthetic of 2014, a time that doesn’t rightly feel long enough ago to elicit that nostalgic longing for things past.

But perhaps the most worrying proof of this impulse that’s come to light recently is “March 2020 nostalgia”. Yep you heard that right. People are actually nostalgic for the early days of the pandemic. The #firstlockdown.

There’s a subset of TikTok that’s awash with montages of House Party, Tiger King and whipped iced coffee, all set to the Benee’s Supalonely, one of the top trending songs of March-June 2020.

Talking about the phenomenon, Robyn, 23, explains that she “was spending a lot more time outside, taking the dog for lots of walks… I was just a lot happier’, while Will, 18, claims to ‘miss the novelty of the first lockdown’. Weird right?

But the weirdest thing about all of this is that I kind of get it. Even though everything is objectively way better now, thinking about Zoom quizzes and banana bread does give me the warm fuzzies … Maybe it’s rose-tinted glasses? Maybe it’s a form of Stockholm syndrome? Maybe it’s a trauma response? Or maybe we’ve simply run out of eras to be nostalgic for, and we’d rather look back on a moment that was objectively shit than exist in the present?

But the best explanation I’ve come up with isn’t about the past or the present: it’s about the future. Because one of the key differences between where we are now and where we were two years ago is that, despite it being really scary, we were all more optimistic back then. Blissfully ignorant, we thought we’d be back to work and school in a matter of weeks. But the more we get to know this virus, the less we feel we’re able to predict it. Now, two years on, the future feels pretty daunting.

And it’s not just the pandemic. What’s really striking about this moment is that Gen Z are the first generation to grow up expecting the world to get worse in the future – not better. 43% of them believe the environment is past the point of no return, and 59% are not convinced that changing their behavior will make any difference to the planet. In Deloitte’s 2021 global Millennial and Gen Z survey, pessimism about social and political climates also reached the highest levels ever recorded, with more than four in 10 respondents expecting worsening situations. And now they’re watching a huge humanitarian crisis unfold before their eyes in Ukraine, which many worry will end up taking us back to the war-torn Europe of the 1930s and 40s. In short, the future is looking pretty bleak. The prevailing narratives aren’t about the opportunity to build a better world, but about trying to reverse the damage we’ve already done, not something that inspires a good deal of hope and optimism.

There are, of course, some voices in our society that are looking to the future with excitement: voices that are giving us a vision of what a better tomorrow could look like, and drawing roadmaps for how we get there. Unfortunately, the loudest of these voices belong to middle-aged men whose futurism seems to be nothing more than a thin veil for the promotion of their own vanity projects.

While Mark Zuckerberg would have us retreat from our damaged physical world into a (Meta-owned) virtual one, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk espouse the virtues of a new age of Space Colonialism, with they themselves at the helm of our new ‘spacefaring civilization’. These are not the sort of futurist visions that will have the power to galvanize our youth, not least because Gen Z have an aversion to everything the men promoting them represent: a poll last year showed that 39% of Americans under 30 believe that the existence of billionaires is an actively bad thing, as opposed to just 16% who professed the opposite view. Pair that with the fact that a flight on Virgin Galactic currently costs around 10 times the average American’s yearly paycheck, and the ambitions of our society’s most ardent futurists look more like elitist fantasies.

So where do we go from here? Because when you step back and take stock of the options available to Gen Z about the type of future they want to subscribe to, they are not only limited, but profoundly uninspiring. It’s either:

Embark on a grueling losing battle with pandemics, climate change, and social and political inequality;

Give up on earth in pursuit of limitless growth in new worlds, while lining the pockets of billionaires; or

Put your fingers in your ears, get dressed up in butterfly clips and lowrise jeans, and listen to Britney

I know which one sounds most enjoyable to me.

In the face of what seems to be a grand societal loss of faith in the future (at least in an earthbound one), it’s no wonder that our youth are turning to the past to get their fix of fun, comfort, and general light-heartedness. But in the long-term, is this obsession with things past sustainable or healthy? Or is it a symptom of pessimism and paralysis that – instead of indulging – we should be fighting against? Perhaps rather than drawing Gen Z in with tie-dye phone cases and Gameboy-shaped fanny packs, we would really be serving them better if we started giving them a vision of what a better future could look like.

Because the future has a brand problem, and, while marketers can’t change the world, we’re damn good at changing the narrative, which is at least a step in the right direction.

Sources:

Katie MacBride, “The power of nostalgia: What science tells us about longing for the past”, Inverse, 2021

“Spotify listeners are getting nostalgic”, For the Record, 2020

Bill Keveney, “Nielsen finds nostalgia fuels interest in classic TV comedies during pandemic”, USA Today, 2021

Allison Pavlick, “How the 20-year rule predicts how you’ll dress”, Thread

Serena Smith, “The lockdown 1 nostalgia has begun”, Vice, 2021

Bobby Duffin, “Climate, Covid and conflict Generational myths and realities”, The New Scientist and King’s College London, 2021

“The Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey”, Deloitte, 2021

Christopher Ingraham, “Young Americans say billionaires do more harm than good”, The Washington Post, 2020